Written by Anna Lewis

Header photo by Jane Hu

Published October 22, 2019

Where can we agree to disagree on whether technology should be used to enhance humanity?

I was introduced to transhumanism by a cyborg. The year was 2002, and Kevin Warwick had just become one of the world’s first cybernetic organisms. An array of electrodes was implanted in his arm and plugged into his nervous system. With his new powers, Warwick could control an artificial hand, with his mind, a continent away. Later that year, his wife also had a device implanted. They became the first humans to have direct nervous-system-to-nervous-system communication with each other. (Today, Warwick is an emeritus professor at Coventry and Reading Universities after a long career in engineering. He has been nicknamed “Captain Cyborg” by The Register, a British tech publication.)

The experiments were provocative. But they paled in comparison with the vision Warwick laid out. I was visiting the University of Reading, where Warwick was advising potential applicants. My gaggle of schoolgirl friends expected to receive tips for our university applications. Instead, we were invited to view aspects of our bodies as impediments to be overcome. In Warwick’s view, communicating via speech was ridiculously primitive. So was living in three dimensions. The idea was to use technology to upgrade ourselves, to overcome the biological limitations of the human condition.

This grand vision goes by the name of transhumanism. Transhumanists wish for lives of eternal vigor, no suffering, and massively increased capabilities, and they think technology can get us there. They look at genetic engineering, artificial intelligence, brain-computer interfaces, neuropharmacology, and a host of other methods — and they see the potential to overcome aging, and perhaps leave our bodies behind. Wind the clock forward to 2019, and Elon Musk’s Neuralink are on the verge of announcing high bandwidth connection between brains and computers, making Warwick’s DIY electrodes look like a baby step.

Last year, I was at a regular haunt — one of the many techno-hippie communes in San Francisco — and I mentioned that I was mulling some arguments against transhumanism. My interlocutor, a techno-hippie himself, seemed genuinely confused. “I just don’t understand how you could argue against transhumanism,” he said. In that moment, I realized just how much of an entrenched ideology transhumanism has become, especially in the tech-forward, optimistic bubble of the Bay Area.

Proponents of transhumanism think their position is so obvious, arguments for it are unnecessary. For example, Oxford philosopher Nick Bostrom stresses that their project is just a natural extension of what we already try to do with medicine and technology. Bay Area writer Eliezer Yudkowsky suggests that there is no “trick” here: life is good, death is bad; well-being is good, suffering is bad. From this perspective, arguments against transhumanism are almost unthinkable. How could you argue against technology that decreases human suffering?

In contrast, since moving to the East Coast, I haven’t found much but disdain for transhumanism. The prevailing view I’ve encountered amongst diverse intellectuals in Boston, New York, and D.C. seems to be that transhumanists are uncaring, misguided nut jobs, who just don’t get it.

This disconnect has practical implications. If we believe we can control technology through regulation or social norms, then we’re faced with questions of how we should seek to influence the development and deployment of technologies that can support transhumanism. If transhumanists want others to back their vision, they need to be able to defend it against those who think they are nut jobs. And, since many new technologies are being developed by transhumanists, opponents must engage with transhumanists if they want to affect what gets built.

Yet, as the comment from my friend the techno-hippie suggests, we lack even the ability to see where we can Agree to Disagree. Both sides need a better understanding of the disconnect — and soon, because many relevant technologies are no longer science fiction.

Science Fiction Visions Made Real

The 1997 movie Gattaca, a near-future dystopia written and directed by Andrew Niccol, is a chilling portrait of what society might look like when people choose which children are born based on how “good” their genes are. The movie shows parents choosing between embryos using probabilistic profiles based on their genetics: in other words, the parents can’t choose a child with a specific IQ level, but they can choose a child who’s likely to have a high IQ. Gattaca’s hero is a character with a 99% chance of serious heart problems, who is born only because his parents choose not to look at his pre-birth probabilistic profile. As he grows up, society assumes the hero will be a “failure” based on his genes. He has the opportunity to succeed professionally only because he impersonates another citizen with a “healthy” genetic profile.

Back in the “real world,” as of 2018, parents using in vitro fertilization can pay a company called Genomic Prediction for the earliest version of Gattaca-style technology. The company scores embryos for their genetic propensities of common diseases. This includes intellectual disability, which is based on a very low value for a score that probabilistically predicts number of years of education. (They have the ability to screen for kids who are likely to excel at school, but they seem to be holding off on selling that until there’s a broad consensus that it’s ethically acceptable. Earlier this year, an interviewer asked Genomic Prediction co-founder Stephen Hsu whether there are any scenarios in which they’d screen for high IQ, and he responded: “We feel like society is not ready for it.”) In my opinion, these scores are lousy predictors at present, and the scores will always be probabilistic, but they will improve dramatically.

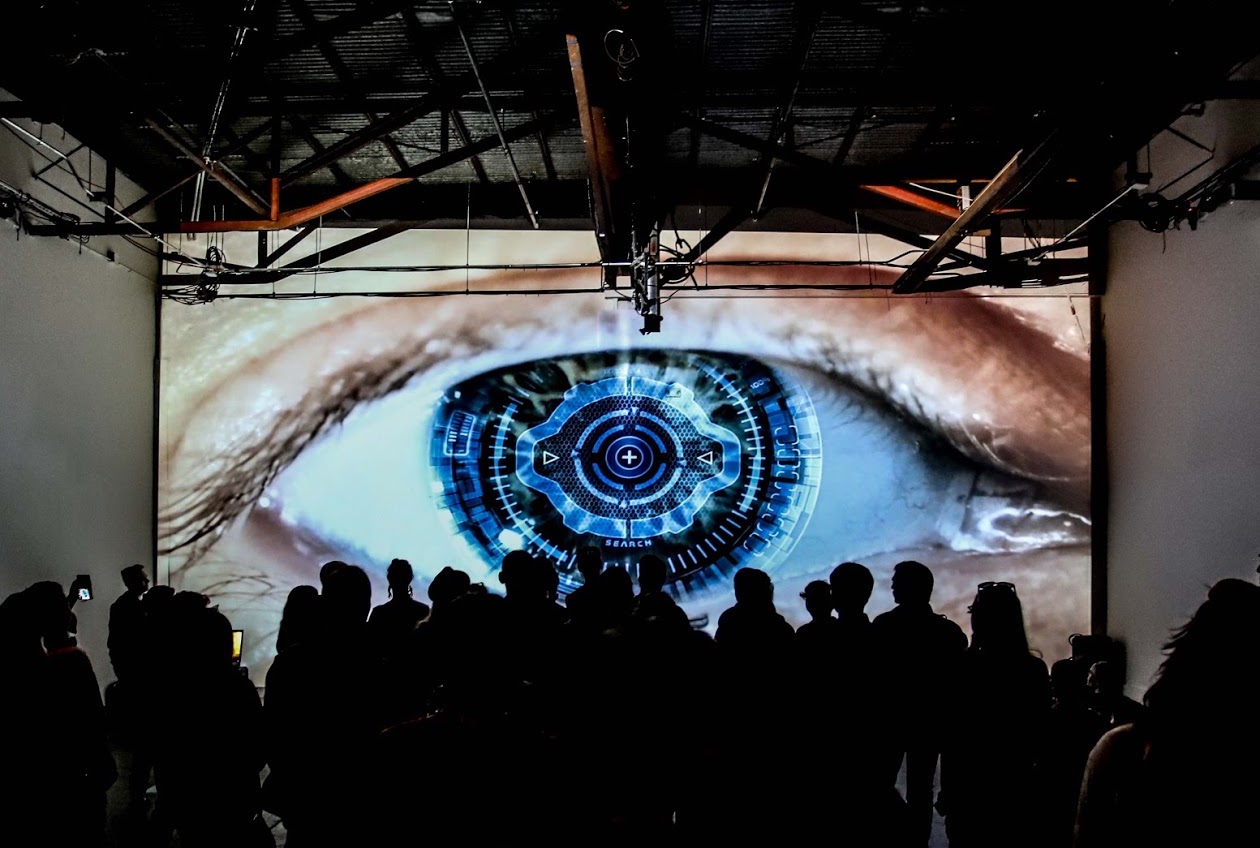

Other science fiction stories envision ubiquitous brain-computer interfaces, as in William Gibson’s 1984 novel Neuromancer, or Masamune Shirow’s 1989 manga Ghost in the Shell. Shirow’s heroine has a fully prosthetic body; Gibson’s hero can access the Internet using his nervous system. Today, we’re seeing early development of those technologies. Want to control stuff with your mind? For those with an off-the-shelf electroencephalogram (EEG) headset like the NeuroSky, there’s an App Store full of possibilities — programs like MindWriter (“Write With Your Mind”) and EEG Meditation (“dumbbells for the development of the mind”). Meanwhile, researchers like Youssef Ezzyat at Swarthmore have improved human memory using external neural stimulation.

It’s not just small startups and academic researchers. Facebook, Google, and Elon Musk are all investing heavily, backing a broad range of technologies. Many transhumanists are ecstatic about these advances; opponents are left to point out issues. Their objections can be gathered into three main considerations.

Your child's best friend might be a robot. Your child might become a robot. You might become a robot.

Photo by Andy Kelly

Objection 1: “Transhumanists' Overconfidence Will Make Things Worse”

In 2004, Stanford political scientist Yoshihiro Francis Fukuyama called transhumanism “the world’s most dangerous idea” in the print edition of Foreign Policy. His argument directly attacks transhumanism’s inherent optimism as overconfident: we could make things worse by accident, even when we intend to make them better.

Humans have cultivated roses for centuries. Over that time, some types of roses lost their distinctive scent. They were bred for appearance, and many gardeners — as they focused closely on improving the flowers’ physical beauty — didn’t realize the scent could be bred away until it was gone. As we modify humanity, we may encounter similar problems. In a world like Gattaca where we pick which humans come into existence, we might be tempted to create humans with less capacity to feel anger or emotional pain. But how do we know that we wouldn’t thereby also reduce the capacity to love?

Of course, it’s true that we can’t predict the effects of our actions. Optimism is by definition a bias. But so is pessimism — so the appropriate response is to seek to minimize bias. How?

By considering a broad set of possible scenarios. At genetic conferences, I’ve heard the interjection, “but Gattaca!” when new techniques were introduced. So dystopian science fiction has played an effective role in scenario-planning. But we need many more possible scenarios projected and imagined, among a highly diverse set of people, in as much detail as possible, so that we can foresee a higher proportion of risks. Both transhumanists and pessimists have essential roles to play.

Objection 2: “Transhumanists Don't Realize The Benefits of Life's Constraints”

The second anti-transhumanist argument is that, in trying to rise above the human condition, we give up too much. In a 2004 article titled “The Case Against Perfection,” Harvard political philosopher Michael J. Sandel argues that the “drive to mastery” the transhumanist project embodies will destroy the ethic of “giftedness,” at high cost. He suggests that we will lose our ability to be humble in seeing our talents as things we are lucky to have; that we will gain unwanted additional responsibility to become more than we are; and that we will lose the sense that we share our fate with the rest of humanity.

When he wrote that article, Sandel was serving on the George W. Bush administration's President's Council on Bioethics. And it’s no coincidence that this line of argument usually comes from politically conservative voices. For many conservatives, the constraints on human nature dictate the appropriate political strategy: small changes that work within the confines of the type of creature that we are. From this perspective, bold visions involving massive change — like those of Marx — are destined to fail because they assume that humans can adapt to any social circumstances.

In the biotech context, conservative voices such as Sandel’s don’t just say that human nature must be taken as a pragmatic constraint. They show a positive attachment to those constraints as providing a vision of the good life.

Given this argument’s connection to a conservative ideology, it is perhaps unsurprising that many transhumanists — who tend to be liberal — are unconvinced. After all, there are alternate visions of the good life beyond accepting what nature has given us. And indeed, the view of life that Sandel sets up to shoot down — the “drive to mastery” — smells very similar to a take on the good life common among the liberal techno-optimist crowd: a philosophy of personal growth as a good in its own right; exploration not in reference to given limits, but for its own sake.

Either extreme — full acceptance of the role of fortune on the one hand, or seeking to completely overcome the hand we’ve been dealt on the other — is untenable. Fully submitting to nature’s caprice is not consistent with developing medicine at all. Yet nurturing our ability to acknowledge and accept the role of luck also makes sense, not least because the drive to mastery will always be frustrated by randomness.

Objection 3: “The Transhumanist Project Will Compound Existing Inequalities”

The third set of arguments against transhumanism focus on their negative consequences for society, and suggest that a large faction of technology optimists haven't adequately considered social consequences. In 2018, the Cambridge physicist and cosmologist Stephen Hawking died and left behind a book predicting an unenhanced underclass. After all, the worst-off continue to lack access to health care, to education, to the basics that add up to a dignified life. So perhaps attention to the transhumanist cause distracts from this and risks compounding the situation.

The transhumanist project both introduces new ways that some can be disadvantaged with respect to others — those that have, versus those who do not have the enhancements — and is also likely to compound existing inequities, because enhancements will likely be available to wealthy users first.

With prominent voices such as Peter Thiel and Elon Musk advocating for both transhumanism and libertarianism, a libertarian transhumanism appears on the ascendant. But there are alternatives. Some modern transhumanists advocate for "democratic transhumanism."

One standard response from transhumanists is to insist that though the best-off might get the advantages first, these will later become available to the less well-off, because that’s a common trajectory for consumer technology. Laptop computers and smartphones, for instance, were once available only to the rich and are now found in most social classes all over the world. Non-believers roll their eyes to this response (I have personally experienced more-than-metaphorical eye rolls in discussing this very point), as it compounds the “usual story” of trickle-down progress with the worn-out idea that innovation and technology are the solution to all our problems.

Additionally, while many transhumanists insist that getting enhanced will be a free choice, those decisions will impact others in any zero-sum competition. Even in today’s athletic industries, like competitive cycling, we see this zero-sum problem with doping scandals: the decision not to dope has sometimes seriously affected athletes’ chances.

These criticisms are largely aimed at a libertarian version of transhumanism. With prominent voices such as Peter Thiel and Elon Musk advocating for both transhumanism and libertarianism, a libertarian transhumanism appears on the ascendant. But there are alternatives. Some modern transhumanists advocate for “democratic transhumanism,” notably bioethicist James Hughes in his book Citizen Cyborg: Why Democratic Societies Must Respond to the Redesigned Human of the Future. In the future he imagines, enhancement technologies are available to all who want them.

This may sound radically different from the world we live in today, but such bold visions are not new in transhumanism. If we look back at the work of transhumanism pioneer FM-2030 (born in 1930 under the name Fereidoun M. Esfandiary), transhumanism was a means to achieve a truly universal society based on non-violence. FM-2030 believed that biology played a role — as aging and death are very violent, and family structure prevents the universal — but his vision, outlined in Up-wingers: A Futurist Manifesto, included vast changes to our political and socioeconomic systems, including children being raised in common and an absence of any permanent settlements.

While discussing these potential effects on privilege, inequality, and social structure, it becomes obvious that transhumanism is much more than a technological project. Many of the issues it raises are social, and as Oxford’s Nick Bostrom suggests in his “Transhumanist FAQ,” these social problems need social solutions.

Transhumanists who want technology to do more than pour gas on the flames of existing social issues need to own a radical political vision and be committed to it. The work involved is only partly technological. And if these technologies are imminent, political action to achieve a broader vision is urgent.

Integrating The Criticisms

These arguments against transhumanism cover a huge breadth of issues: optimism about the impact of technology, vision of what gives life meaning, and the type of society we want to live in. Perhaps it’s not surprising that it’s such a divisive issue.

Seventeen years ago, when I was a schoolgirl encountering a cyborg in an unassuming corner of England, the transhumanist vision seemed outlandish. It also seemed exceedingly fringe. Recent life in the tech-focused Bay Area has shown me that, at least within that influential bubble, the vision is far from fringe — it borders on the mainstream. In fact, it’s so close to mainstream in Bay Area biotech that it’s easy to lose track of why those outside the bubble continue to view it as outlandish.

That sense of outlandish-ness can, and should, be usefully channeled. As with any belief system, engaging with those who think differently helps one realize what one actually stands for, and in turn can goad us to action. The argument that constraints on human nature provide a desirable moral backdrop to life should make us wonder which constraints we should, and which we must, accept. A sensible response to the argument that transhumanists are optimistic to the point of hubris is to conduct extensive scenario modeling. The argument of negative social consequences demands the development of the non-technological side of the vision. To develop a truly humanistic transhumanism — and humanistic biotech to go with it — there is much to be done.

This article will be included in Issue One of The New Modality, in print! You can buy your copy here.

Transparency Notes

This piece was written by Anna Lewis, who received her Ph.D. from Oxford in 2012 in Systems Biology. After that, she spent several years living in the Bay Area while working in the genetics industry. She is now a joint fellow-in-residence at the Safra Center for Ethics and the Bioethics Center at Harvard University, investigating the potential societal implications of genetic technologies. Transhumanism was in the background of her work in tech, and now in ethics. We published this piece because, as it delves into the ethics of transhumanism, it can help readers develop their perspectives about the advances in biotech we're seeing today.

The article was edited by Lydia Laurenson, editor in chief of The New Modality. It wasn't fact-checked, but we ran it past a couple of community members with different technical expertise before publishing. For more about our transparency process, check out our page about truth and transparency at The New Modality.