“California Dec 5 2017,” painted by Suelyn Yu. Oil on wood panel, 2018.

Climate Change Heroism In The Insurance Industry

How The Insurance Industry Can Help Us All Build Climate Resilience

Written by Shanna McIntyre

Illustration by Suelyn Yu

Published September 19, 2020

Climate change is no longer a conceptual forecast that lives in research papers or government reports. It has arrived, in the form of more extreme natural disasters. In California, we’ve witnessed this as an abrupt change in wildfire behavior that’s affecting millions. The state has made admirable strides in helping communities grapple with the existential threat they now face, but the private sector has some surprising tools to offer as well.

[[This article appears in Issue One of The New Modality. Buy your copy or subscribe here.]]

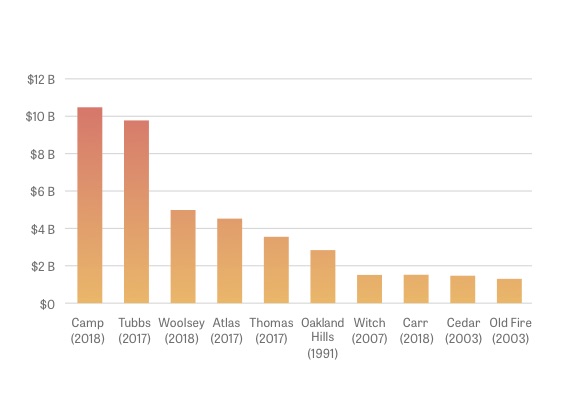

In order to grasp the scale of problem, and how the private sector has been affected, it helps to look at how California’s wildfire losses over the last three years stack up with previous wildfire events in the state:

Data source: Insurance Information Institute and California Department of Insurance

This graph shows how more recent wildfires have led to much greater financial losses — to the tune of billions of dollars. What’s going on?

Many factors are leading to more severe wildfires, and not all are related to climate change. Some problems stem from other types of short-term thinking: For instance, over the last fifty years, many homeowners put themselves into harm’s way by building or buying homes in the wildland-urban interface (WUI) where development encroaches into wilderness areas. These areas often have high brush hazards, but since the late 1970s, the number of Americans living in WUI lands has doubled (one likely explanation is that those areas are more affordable).

But the biggest drivers of the new fire behavior are climate-change-related. Record temperatures are drying out the fuel load across the state, and the fire season is getting longer.

Kevin Trenberth, a scientist in the climate analysis section of the National Center for Atmospheric Research (a government body funded by the National Science Foundation), told Inside Climate News that “In the West, they used to talk about a fire season. The fire season used to be 60 days, then 90 days, and now they think it's year-round. There's no pause." Climate scientists have predicted this exact outcome, and they now predict that it will become even more extreme over the next decades.

The government is responding where it can. One government body, The California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (commonly referred to as Cal Fire), is working to identify communities that are newly at risk. Cal Fire offers guidance that encourages homeowners to take actions (like reducing brush near the home) to reduce their fire vulnerability. But it will likely be years before those efforts have any observable impact on the spiking state-wide wildfire loss totals.

The fires’ severity caught the insurance industry off guard, too — not just the government. No insurance companies had models that predicted these losses, because the models were based on data from the pre-climate change world. Climate change has rendered the most commonly used wildfire models to be far less accurate than what the industry needs. The newly realized uncertainty means that the industry now operates blindly wherever there’s potential wildfire risk, and this has left most insurers with a very short list of choices:

- Choice 1: Dramatically increase premium rates in hopes of covering the spiking losses;

- Choice 2: Refuse to renew the insurance of homeowners that are deemed to be potentially too risky;

- Choice 3: Face insolvency.

All three outcomes have already been happening. Insurance companies have non-renewed over 340,000 policies in just four years, according to the California Insurance Commissioner (who represents the Department of Insurance, a consumer protection agency). In 2018, a total of 88,187 homeowners were forced to find replacement coverage, often at prices up to 400% higher than what they had paid before.

This has ripple effects in broad swaths of the state. Homeowners are required by their mortgage lenders to have full insurance coverage, and so, as thousands have struggled to find affordable coverage in time (if at all), real estate markets took a hit. Rural communities that rely on retirees are seeing their local economies affected. Loan officer Toni Ryan, who works in rural Placer County, told the Sacramento Bee (a local newspaper) that home buyers are so discouraged, they’ve stopped looking. Restaurants and others in rural areas “are complaining that they’re not seeing the same traffic as they used to.”

But amidst an industry in such disarray, new solutions are underway. Many startups in the world of insurance technology (InsureTech) — like my company, Delos Insurance — hope to create solutions for this new reality by modeling wildfire risks better. This emerging ecosystem includes richer data sets, incorporation of climate science, leveraging artificial intelligence in the models, and digitizing distribution. Our hope is that insurance carriers can now understand the risks far more accurately, in real time, and will be able to quickly offer homeowners data-driven recommendations for mitigating their risk.

Some InsureTech startups are using computer vision on satellite and aerial imagery to build new, more accurate data sets about roof and yard condition. They’re also creating mobile apps that allow for quicker, lower-cost inspections of property conditions. And some (like us) are trying to send regular digital notifications to homeowners about how their wildfire risk is changing, as well as customized recommendations for home-hardening.

The artificial intelligence and digital distribution might be new, but this relationship between insurance and large-scale human behavior is a long-established part of the US economy. Insurers have been quietly influencing our lives for centuries. Before the government inspected homes for safety standards, insurers often played the inspection role. The same is true for many safety features in workplaces; insurers have often helped forecast risk, thereby contributing to the infrastructure that helps people stay safe.

This contribution to infrastructure can be social and cultural, not just physical: for example, liability insurance is cheaper if a company trains its workforce to prevent accidents and lawsuits. Insurers have even intervened in hiring and firing of specific police officers as some officers showed themselves to be a liability to the police department and broader community. In 2010, the mayor of Rutledge, Tennessee, fired the police chief after he was charged with assault — and the mayor told a local newspaper he “had no choice,” because the city was at risk of losing its insurance. In 2017, The Atlantic even published a detailed article with the title “How Insurance Companies Can Force Bad Cops Off the Job.”

Insurance has naturally played this role for a number of reasons. For starters, compared to a government entity, there’s far more financial incentive for insurers to correctly model risks and take action to prevent loss. More accurate risk models, along with risk reduction, will result in more profitable portfolios.

Additionally, private companies can usually act more quickly than governments. For example, the state of California recently issued a report recommending that “at the state and regional level, governments and planners... begin to de-prioritize new development in areas of the most extreme fire risk” (Wildfires and Climate Change: California’s Energy Future). Municipal planners, who must balance a huge array of stakeholders and existing laws, will take months or years to learn how best to manage this task. But meanwhile, skyrocketing insurance costs have already incentivized consumers to choose less wildfire-exposed homes.

Pricing is just the first of many ways the insurance industry can affect consumer behavior. Insurers are in a powerful position to incentivize consumers to build up their own individual climate resilience — for instance, they could require that homeowners take specific home-hardening actions if they want to keep their insurance.

Many insurers already offer discounts for some basic best practices such as clearing defensible space or installing sprinklers. But there are more techniques that can be incentivized via insurance, and the insurance industry is in an unprecedented position to leverage big data to determine exactly what homeowners should prioritize about their behavior. For instance, insurers might be able to use new, more sophisticated wildfire spread models to determine exactly how much a specific home-hardening action will reduce the risk, and offer commensurate discounts.

Hopefully, as long as these new models are built carefully and use high-quality data, all the home-hardening actions that reduce premium rates will add up to communities that are more ready for the effects of climate change. If a government tried to accomplish the same thing through regulation, it could take years — but perhaps it could happen by means of a simple insurance policy contract, fueled by homeowners’ desire to save some money.

The same will be true for other types of climate change impacts on disaster risk, such as hurricanes, storms, floods, and on and on. And for regions that are truly high-risk, with high premium rates to match, conscientious insurers can offer crucial signals to consumers about where the existential danger is, so that consumers make informed decisions about where to live in the first place.

It would be even better if there were more relationships among insurers, academics, nonprofits, and government entities, in order to collaborate on solutions. Three of those entities — academia, nonprofits, and governments — tend to view insurance as a necessary-but-undesirable fourth partner, necessary because of the insurance industry’s financial leverage constraining consumer choices. The collaboration could go further if those other entities also recognized that insurance is a powerful incentivizing machine. Some good examples of recent collaborations include:

- The state of California created an Insurance subgroup in its Tree Mortality Task Force, which is “coordinating emergency protective actions and monitoring ongoing conditions” in order to save more trees;

- Some insurers now give discounts to people who get trained by Firewise, a community program created by the nonprofit National Fire Protection Association.

As someone in the industry who cares deeply about climate change, I hope that the insurance industry finds ways to incentivize change at the system level, not just the personal level. Insurance has a long history of rewarding individual behavior with individual benefits, in the form of premium rate reductions. If insurance can create financial feedback loops for better stewardship of natural resources, improved energy infrastructure efficiency, or even innovation of carbon capture, then it’s possible that a market-based solution can be a powerful factor moving our economy towards seemingly impossible goals. In this way, I believe the insurance industry could truly help us all build a better future.

[[This article appears in Issue One of The New Modality. Buy your copy or subscribe here.]]

Transparency Notes

Shanna McIntyre is founder and chief data officer at Delos Insurance, an insurance technology startup that’s applying satellite data, AI, and climate modeling to natural disaster predictions. Before Delos, she spent more than a decade performing probabilistic analysis of spacecraft system design and performance. Astrophysics was her gateway drug.

Suelyn Yu is a visual artist and climate activist living in Berlin. Her paintings play on the edge of abstraction and realism, inviting the viewer to pause in the tension. Through a micro and macro lens on the natural world, she poses questions about the future we want to live in.

This article was edited by Lydia Laurenson and lightly fact-checked by our editorial team. There's more about our transparency process at our page about truth and transparency at The New Modality.