Can We Pass Our Species IQ Test?

An Interview with Deborah Parrish Snyder of Synergia Ranch

Interview by Sarah Henry

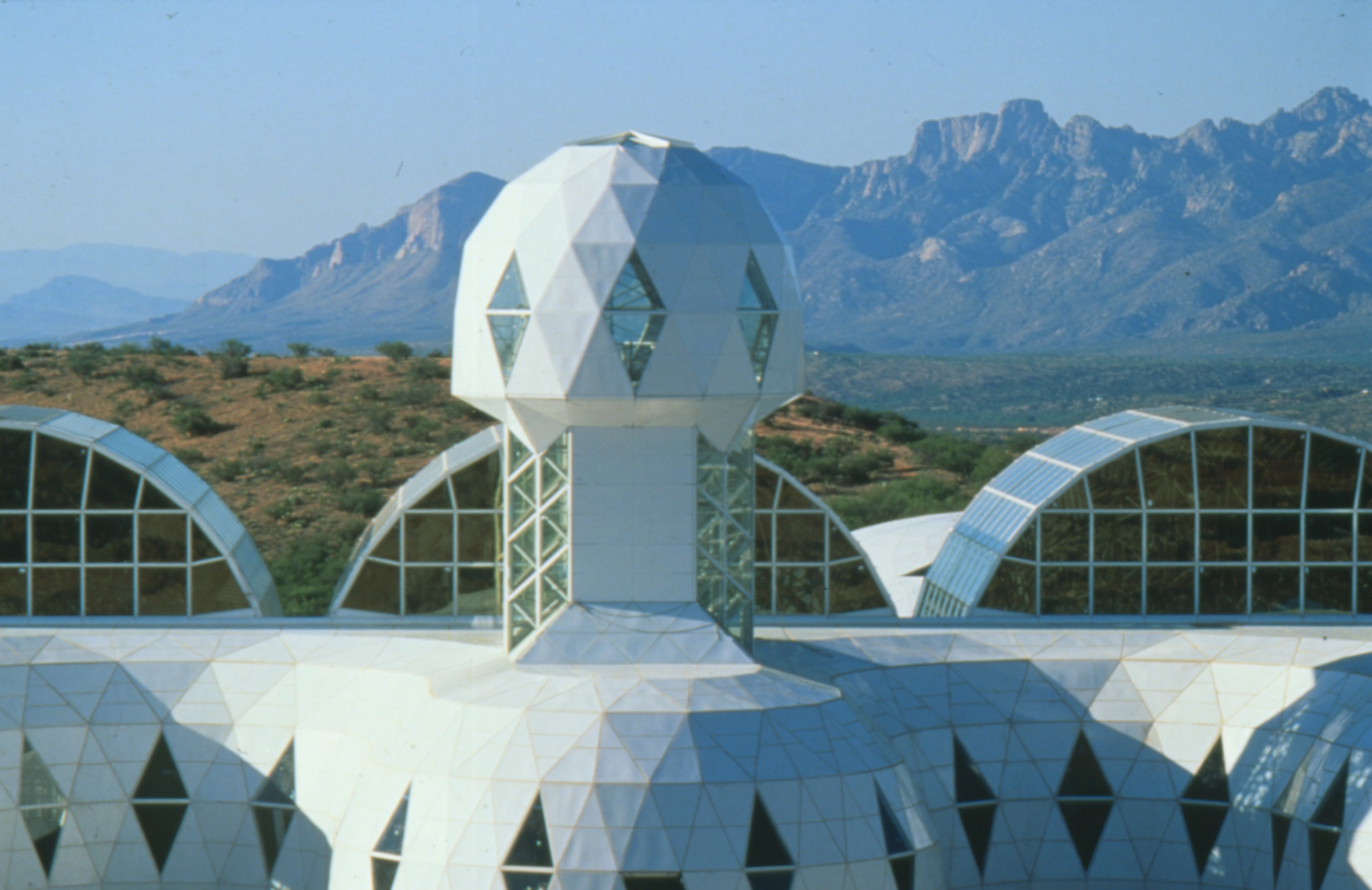

Photo of Biosphere 2 by Gill C. Kenny

Published September 8, 2020

The ambitious, interdisciplinary, global group behind the Institute of Ecotechnics has dedicated decades to ecological innovation — sometimes in the face of hostility and ridicule.

Biosphere 2 was one of the most expensive and ambitious utopian scientific projects of the 1990s. A huge, man-made dome in the Arizona desert, Biosphere 2 was intended as a test to see how humans might cultivate a natural life in the largest closed ecosystem ever built. It acted as a prototype for future space colonization and a research center for holistic permaculture. For two years, eight researchers lived inside the dome, tending to various ecosystems, growing their own food, and researching how a sealed environment might generate everything necessary for life, including oxygen.

[[This article appears in Issue One of The New Modality. Buy your copy or subscribe here.]]

At first, the project excited a remarkable variety of people. Its original funding was $150 million from a billionaire environmentalist named Ed Bass. Then Bass became concerned about the project’s high costs and brought in Steve Bannon — the same Bannon who later became Chief Strategist of Donald Trump's White House — who was then an investment banker specializing in takeovers. After Bannon’s involvement spurred two researchers to sabotage the project and then resulted in some lawsuits, Biosphere 2 was given over to Columbia University, which called it a "major initiative for scientific research and education to address the world's critically important environmental challenges" and stated that the initiative would “create an unprecedented laboratory that will attract scientists from around the world.”

Following those challenges, Biosphere 2 attracted ridicule throughout the late Nineties and by the end of the decade was widely considered a failure. In 1999, Time Magazine listed Biosphere 2 as one of the "100 Worst Ideas of the Century" (along with Prohibition, Ponzi schemes, and hydrogen-filled blimps). Yet in 2020, as ecology pushes to the forefront of the world's most urgent issues, Biosphere 2 is once again in the news. Press outlets including the New York Times have started suggesting that we ought to pay attention to the project's lessons. A documentary called Spaceship Earth recently premiered at Sundance.

“Today I remain optimistic that humans can solve the problems they cause. My optimism, in large degree, comes from my Biosphere 2 experience.”

— Mark Nelson, former resident of Biosphere 2

In 2018, a former Biosphere 2 resident named Mark Nelson published a largely positive account of his experience living in the dome between 1991 and 1993. Nelson describes both problems and tensions he experienced but ultimately points out that, "We are facing a species IQ test that will determine if humans can show the intelligence, resilience and adaptability to be a cooperative, creative part of our planetary biosphere — or whether we are headed to an evolutionary dead-end," and concludes: "Today I remain optimistic that humans can solve the problems they cause. My optimism, in large degree, comes from my Biosphere 2 experience."

But where did the idea for Biosphere 2 come from? Originally, Biosphere 2 was a project by Synergia Ranch, which has been variously described as an "eco-village," a "commune," and even, by some less sympathetic, as a "cult." As for how Synergia Ranch describes itself, it's a "center for innovation and retreats" and a "creative environment for discovery" — in fact, that's what its website says now, because it's still around today.

Synergia Ranch was founded by John Allen and Marie Harding in 1966, in Santa Fe. They wanted a place where they could build tools, companies, theater troupes, and any other project they might need in their quest to envision a more holistic world. They were quickly joined by friends and colleagues. Following the Ranch, Allen and his cohort founded the Institute of Ecotechnics. Allen later wrote in his 2009 book Me and the Biospheres that, “the ecology of technics means evaluating the total system of inputs and outputs from and to the biosphere of any technical system.”

Throughout the years, the Institute has acted as an umbrella organization, convening scholars, activists, and workers to develop projects such as “a rainforest reforestation project in Puerto Rico, an ocean-going ecological research ship, restoration of an over-grazed cattle and horse ranch in the tropical savanna of northwest Australia, organic orchards and regionally-adapted architecture in the high desert country of New Mexico, and an art gallery in London’s Bloomsbury district exhibiting contemporary artists from around the world” (this is from their website, which goes into more detail about all of the above). Since the end of the Biosphere 2 project in the Nineties, the biospherians and their cohort have continued to work on various projects.

I spoke with Deborah Parrish Snyder, a Director of the Institute of Ecotechnics, CEO of Synergetic Press, and longtime collaborator at Synergia Ranch. She manages Synergia’s international conferences, works on pastoral regeneration in NW Australia, and is a Trustee of the Institute for Ecotechnics’ London-based October Gallery. I wanted to know how her various projects had actually happened.

SARAH HENRY: Let’s start from the beginning. How did you get started with John Allen’s group? What was the culture that helped form these projects?

DEBORAH PARRISH SNYDER: I [first] came in contact with this school, you might call it, of Ecotechnics — a synergist kind of new emergent culture — when I was 24. I was living in France, and I came to a project there. [Editor’s note: The 1982 Institute of Ecotechnics' Galactic Conference in Les Marronniers, France, hosted speakers including Buckminster Fuller, Richard Dawkins, the microbiologist Lynn Margulis, and LSD inventor Albert Hofmann.]

“The word sustainability was not in the vocabulary. Nobody said, ‘we're looking to build a sustainable life.’ Ecology was still a new word. Nobody talked about recycling. People just wanted to build.”

— Deborah Parrish Snyder

The ideas that came out of the sixties and seventies were really just emerging. The word sustainability was not in the vocabulary. Nobody said, “we're looking to build a sustainable life.” Ecology was still a new word. Nobody talked about recycling. People just wanted to build. They were looking for alternatives to the nuclear arms race and the military industrial complex. Coming out of the sixties, [people were] trying to find new models for living together, enterprise, art, meaning of life kind of stuff.

A lot of groups were doing that at the time, and a number of groups have had different levels of influence, some broader, like the Hog Farm and the Grateful Dead. The Ecotechnics have been more on a smaller scale, more private, more in the hundreds of people or thousands of people that it might have influenced. I consider the Grateful Dead, and the musical leaders of that emergent culture, the shoulders that we stand on.

SARAH: How has the ecotechnics culture changed over time?

DEBORAH: The [group] went through a lot of changes over the decades. Our main line of work started in New Mexico. A lot of people were reading different metaphysical and spiritual writings from different traditions. So a bit of that influenced us. We first started talking about the biosphere in the sense of our life support system on the planet. Buckminster Fuller's ideas from the [1969 book], Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth, were key to the initial ideas.

There were about five years of building places here in New Mexico, in the desert. We planted an orchard and started these interdisciplinary conferences. There was resistance to the modality of specialization — [we were] trying to break out of this tendency to become specialized. Buckminster Fuller was very adamant that the rise of specialization in our academic systems was the end of education.

Maybe 250 people have come through our different projects around the world. Some were with us for a number of years, putting in time and living on different projects, and other people would come through for nine months in training programs, or volunteer for three months in the summer.

John Allen, one of our founders, had traveled around the world and studied a number of traditions, as well as studied at Harvard Business School and at Colorado School of Mines. He's kind of a pioneer of science, a modern-day [Vladimir] Vernadsky kind of guy. [Vernadsky was an interdisciplinary Russian geochemist and mineralogist who, according to Britannica, is “considered to be one of the founders of geochemistry and biogeochemistry.”] John started to put together his business school side of things with his interest in metaphysics and spiritual traditions. He could see there had to be something to address the biospheric big picture. He started working with people to come up with this intentional community, though they weren’t called intentional communities in those days.

Theatre was a really important line of work [at the ranch]. They wrote plays. They did original plays, and translated plays. They also had a construction company, and they built the buildings at the ranch. They planted a farm. There were like 25 people living here at one point. Every year they would do a conference on something like mountains, or the rain forest project they did in Penang. Attendees included Bucky Fuller, William Burroughs, astronauts, cosmonauts, and engineers.

They had a four-four-four system at the Ranch. You had four hours working on [ranch-related] enterprise. You had four hours working on art or theater, and then four hours working on your own enterprise, whatever that was.

[Aside from the ranch], people were going off to different biomic areas to do demonstration projects. To do so, we worked with venture capital. Somebody would come in as a venture capital partner and purchase the property and own the title, so there was security on the investment. There would also be some seed capital to start a business with operating expenses. However, whatever that business was had to become self-sufficient pretty quickly.

SARAH: Why venture capital? Who was the first venture capitalist?

DEBORAH: Well, Marie [John's wife] and he bought the ranch. They would buy the property and start an operating company, through which some people would run the project. But then Ed Bass came along, and he had some significant amount of money. He was the first business partner and made the first big investment in the compound here in New Mexico. And for 20 years, we've built a number of properties together around the planet. He wasn't the only investor. The Heraclitus, the ship we built, was entirely raised by volunteers going out and getting donors and sponsors. It's wholly owned by the Institute of Ecotechnics.

Venture capital is really important, though. Today that's very, very difficult to find. What's harder to find is property. Those are key elements for any long-term sustainable project. You don't want to set up a project on a property that you're renting. An important part of the formula was ownership.

With property, you have power. You have political power in the community. And the projects themselves are meant to become demonstration projects about whatever is going to work in that area.

It helps to have people with vision around you. The “Tincture Effect” is important in emergent culture. There's a famous story attributed to Mullah Nasruddin [a Persian folk character in the Sufi spiritual tradition, who reportedly lived in the thirteenth century]. If you visualize a lake, and there's Mullah. He's got a cup of yogurt. He's pouring it in the lake and all these people come by and say, "Mullah, what's the matter with you? What are you doing?" And he says, “Well, what if it takes?" So the Tincture Effect is, maybe you can make yogurt out of a lake: There's no one answer, or one thing that makes it all work. It's the synergy, and it's whatever works for you, whatever clicks.

But the other key thing for all of these projects was that the task was very clear. If you don't have a clear task, and you don’t have a coalescence of wills around that task, then it's very difficult to make things happen. People always ask why our projects worked when so many others failed. That is the reason.

SARAH: Did the group feel particularly cohesive? Like a commune, a collectivist group, or a religion? Was there something else binding you all aside from the goals of the projects?

DEBORAH: I’m not sure how folks felt back in the seventies, but for me it mainly feels like a group of individuals united in the hope of the impossible. Religion and dogma are not on the menu. We’re more like Benjamin Franklin’s Society of the Free and Easy.

SARAH: Let’s talk a bit about Biosphere 2. I read that the idea for Biosphere 2 was presented at the 1982 Galactic Conference for the Institute for Ecotechnics. Was that cross-use intentional? Are there strategies in place for having projects overlap with one another? Or owning the platform?

DEBORAH: I think everything in life overlaps. Synergy is based on the result being greater than the sum of all its parts. The combination of the projects leads to planetary thinking. People that come to one project want to go and spend time on other projects. There is a lot of cross-fertilization. It’s key. That’s synergy.

Over decades, the interdisciplinary Ecotechnic conferences built the intellectual capital that went into design and building Biosphere 2. The preliminary design ideas for a closed system were presented at the 1982 conference by Phil Hawes [an architect who studied with Frank Lloyd Wright, who is now at the San Francisco Institute of Architecture].

SARAH: During the development of Biosphere 2, a group of people from the Institute met with Russians that had been working on a similar closed ecosystem project. That was right around the end of the Cold War, and seems like a big political move. Are there other examples where politics intersected with the projects? Did you ever have to navigate politics?

DEBORAH: One of the things we made sure of was that we weren't aligned with any major political group. We tried to be apolitical in terms of any positions. Of course, it's clear that we're all Democrats, but we have had a policy of always remaining neutral when it comes to business, because everybody is part of the solution. There are ways to operate without bucking the system. For all our projects, we engage in local politics when it comes to land-use and long-term planning, but we are not a political organization.

When it came to Russia — because we were a private company, we were able to just go to Russia as tourists. I was on one of those trips. Glasnost had just happened. I think Gorbachev had just resigned, so it was like '88-89. It was truly an enlightening experience. One of the things that was really important to everybody in these projects, and managers especially, was to know the world, to travel, to be able to study different cultures, to understand the politics, and to accomplish the task. The Russian scientists, like Vladimir Vernadsky people, were above politics. Vernadsky was not killed [although he was imprisoned during the Russian Revolution], because he was so brilliant. He founded five different major scientific institutions and educational institutions. He was venerated in the East, as Darwin is venerated by most people in the West. These scientists were more like philosophers; they're not bureaucrats, per se. We were able to meet because they could come to our hotel. We couldn't go to their facilities.

SARAH: Where are you seeing opportunities today, like the ones that were available when the ranch started, when the institute started? Real estate is expensive now, and we know how difficult it is to get venture capital. Do you see other areas where opportunities are bubbling up?

DEBORAH: There is a full-on movement that is occurring, that is maybe not articulated well, but it has to be. There is a bit of a resurgence on regenerative agriculture research. The economic movements with alternative currencies — those are interesting because they are breaking, or trying to break, the world market monetization of the planet. Festival culture is really interesting. I think Burning Man was one of the first breaks into a new modality, a new kind of a life that could exist, because of the no-money exchange.

“We have to change the mass perception of understanding that everything is connected. I don't know how that's going to happen. Is it going to take a complete collapse of the system?”

— Deborah Parrish Snyder

We have to change the mass perception of understanding that everything is connected. I don't know how that's going to happen. Is it going to take a complete collapse of the system?

The economics of a low cost of living are important. [At Synergia,] we work from our projects and do not commute. There's going to be major movements around the planet because of climate change. People innovating in low energy, housing, doing more with less, that kind of innovation is where the real changes are going to happen.

[[This article appears in Issue One of The New Modality. Buy your copy or subscribe here.]]

Transparency Notes

This interview was conducted and edited by artist, writer, and researcher Sarah Henry. It was edited and lightly fact-checked by the Issue One editorial team, and Deborah Parrish Snyder was given the opportunity to review her statements before publication. There's more about our transparency process at our page about truth and transparency at The New Modality.